The Language of the New Testament: Unveiling Its Origins

The New Testament, a cornerstone of Christian faith, was primarily written in Greek, specifically Koine Greek, which was the common dialect of the Eastern Mediterranean during the first century. This choice of language not only facilitated the spread of its teachings across diverse communities but also reflected the cultural and linguistic landscape of the time. Understanding the linguistic roots of the New Testament enriches our comprehension of its messages and the historical context in which it emerged.

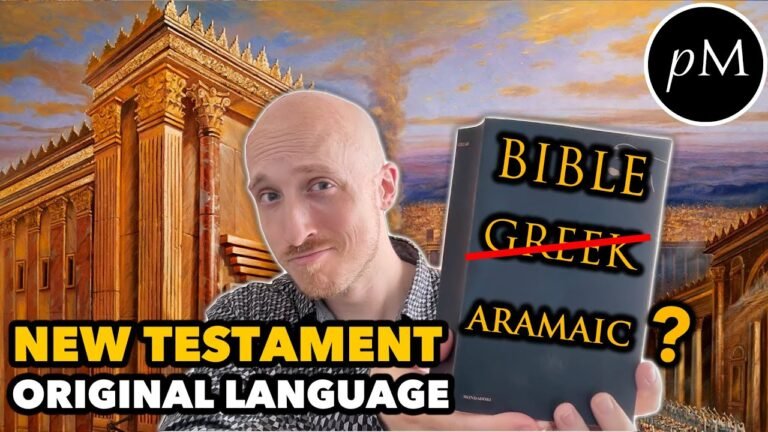

In what language was the New Testament originally written?

The New Testament was originally composed in Greek, a fact widely accepted among biblical scholars. While some debate exists regarding the possibility of certain passages being initially written in Hebrew or Aramaic, the predominant view remains that Greek served as the primary language for this foundational Christian text. This linguistic choice not only reflects the cultural context of the time but also facilitated the spread of Christian teachings across diverse regions of the ancient world.

Was the Bible composed in Hebrew or Aramaic?

The Bible is primarily composed of texts written in Hebrew, particularly the Old Testament. This ancient language reflects the culture and history of the Hebrew people, capturing their religious experiences and traditions. Hebrew serves as the foundation for many of the narratives, laws, and prophecies that shape the Jewish faith.

In addition to Hebrew, some sections of the Bible were penned in Aramaic, the likely spoken language of Jesus and his contemporaries. This inclusion highlights the linguistic diversity of the time and underscores the cultural interactions that influenced the biblical narrative. Meanwhile, the New Testament was originally crafted in Greek, further illustrating the evolution of language and thought within early Christianity.

Did Jesus communicate in Hebrew or Aramaic?

The language spoken by Jesus and his disciples is widely recognized by scholars as Aramaic, a Semitic language that flourished in the region during the first century AD. Aramaic served as the lingua franca of Judea, allowing for communication among diverse populations. This commonality of language was imprescindible in facilitating the spread of Jesus’ teachings throughout the region.

In the Galilean villages of Nazareth and Capernaum, where Jesus conducted much of his ministry, Aramaic was the everyday tongue. These communities were deeply rooted in Aramaic culture, which influenced not only the daily lives of the people but also the religious practices and teachings of the time. The language’s prevalence in these areas underscores its significance in the context of Jesus’ message.

While Hebrew was still used in religious settings and scripture, it was Aramaic that resonated with the common people. This connection to the everyday language allowed Jesus’ teachings to be more relatable and accessible, fostering a deeper understanding among his followers. The linguistic environment in which Jesus operated played a pivotal role in shaping his ministry and its enduring impact.

Discovering the Roots of Biblical Texts

Delving into the rich tapestry of biblical texts reveals a fascinating journey through history, culture, and language. Each verse is a window into the ancient world, reflecting the beliefs, struggles, and aspirations of the communities that shaped them. By exploring the historical contexts and linguistic nuances, we uncover the profound connections between these sacred writings and the lives they touched. This exploration not only deepens our understanding of religious traditions but also invites us to reflect on the timeless themes of faith, morality, and humanity that resonate across generations.

Tracing Ancient Tongues Through Scripture

The study of ancient languages through scripture reveals a rich tapestry of human thought and culture, bridging gaps across civilizations and eras. By examining sacred texts, linguists and historians uncover the evolution of languages like Hebrew, Greek, and Latin, which not only convey spiritual teachings but also reflect the social and political climates of their times. This exploration illuminates the connections between diverse cultures, showcasing how language shapes identity and belief. As we trace these ancient tongues, we gain insights into the shared human experience, fostering a deeper appreciation of our collective heritage and the enduring power of words.

Exploring Linguistic Foundations of Faith

Language serves as the bridge between our inner beliefs and the world around us, shaping the way we articulate faith and spirituality. Through the intricate tapestry of words and meanings, we find that different cultures express their spiritual experiences uniquely, yet many core concepts resonate universally. By delving into the linguistic foundations of faith, we uncover not only the nuances of expression but also the shared human quest for understanding and connection. This exploration reveals how language not only reflects our beliefs but also influences them, inviting us to consider the profound impact of words in our spiritual journeys.

Decoding the Messages of Early Christianity

The early Christian community was characterized by a rich tapestry of beliefs, practices, and symbols that conveyed profound spiritual truths. Central to their message was the idea of salvation, which was expressed through the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. This narrative not only provided hope to believers but also served as a rallying point for a diverse group of followers seeking meaning and purpose in a tumultuous world. The use of parables and teachings highlighted the transformative power of faith, emphasizing love, forgiveness, and the promise of eternal life.

In addition to verbal teachings, early Christians employed visual symbols to communicate their faith. The fish, for instance, became a secret sign among believers, representing Christ and the call to be “fishers of men.” Such symbols offered a way to identify and connect with one another, especially in times of persecution. The richness of these symbols reflects a deep understanding of the human experience, providing comfort and a sense of belonging to those who embraced them.

As early Christianity spread, its messages evolved, adapting to various cultural contexts while retaining core tenets. The letters of Paul and the writings of the Church Fathers reveal an ongoing dialogue about faith, morality, and community life. These texts not only served as theological foundations but also as practical guides for living out the Christian message in everyday life. Ultimately, the early church’s ability to decode and communicate its messages effectively laid the groundwork for a faith that would endure and flourish for centuries to come.

A Journey Through Scripture’s Original Language

Exploring the original languages of Scripture unveils a rich tapestry of meaning that transcends mere translation. Each word in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek carries nuances that offer deeper insights into the texts we hold sacred. By immersing ourselves in these languages, we gain access to the cultural and historical contexts that shaped the messages, allowing us to appreciate the Scriptures in ways often overlooked in modern translations.

Delving into the linguistic intricacies reveals how specific terms and phrases reflect the beliefs and practices of ancient communities. For instance, the Hebrew word “shalom” encompasses not just peace but also wholeness and completeness, enriching our understanding of its usage throughout the Old Testament. Similarly, the Greek term “agape” signifies a selfless, unconditional love that challenges contemporary interpretations of the concept. Such revelations remind us that language is not merely a tool for communication; it is a vessel for profound spiritual truths.

As we navigate this journey through Scripture’s original languages, we are invited to engage more deeply with our faith. Understanding the original texts fosters a greater appreciation for their timeless wisdom and invites us to reflect on our own beliefs and practices. Ultimately, this exploration not only enhances our comprehension but also deepens our connection to the divine narrative that continues to inspire and guide us today.

The New Testament, a cornerstone of Christian faith, was primarily written in Greek, specifically Koine Greek, which was the common language of the Eastern Mediterranean during the first century. This choice not only facilitated its spread across diverse cultures but also allowed early Christians to communicate their beliefs effectively. Understanding the linguistic context of the New Testament enriches our appreciation of its messages and the historical backdrop against which it emerged, highlighting the profound impact of language in shaping religious thought and community.