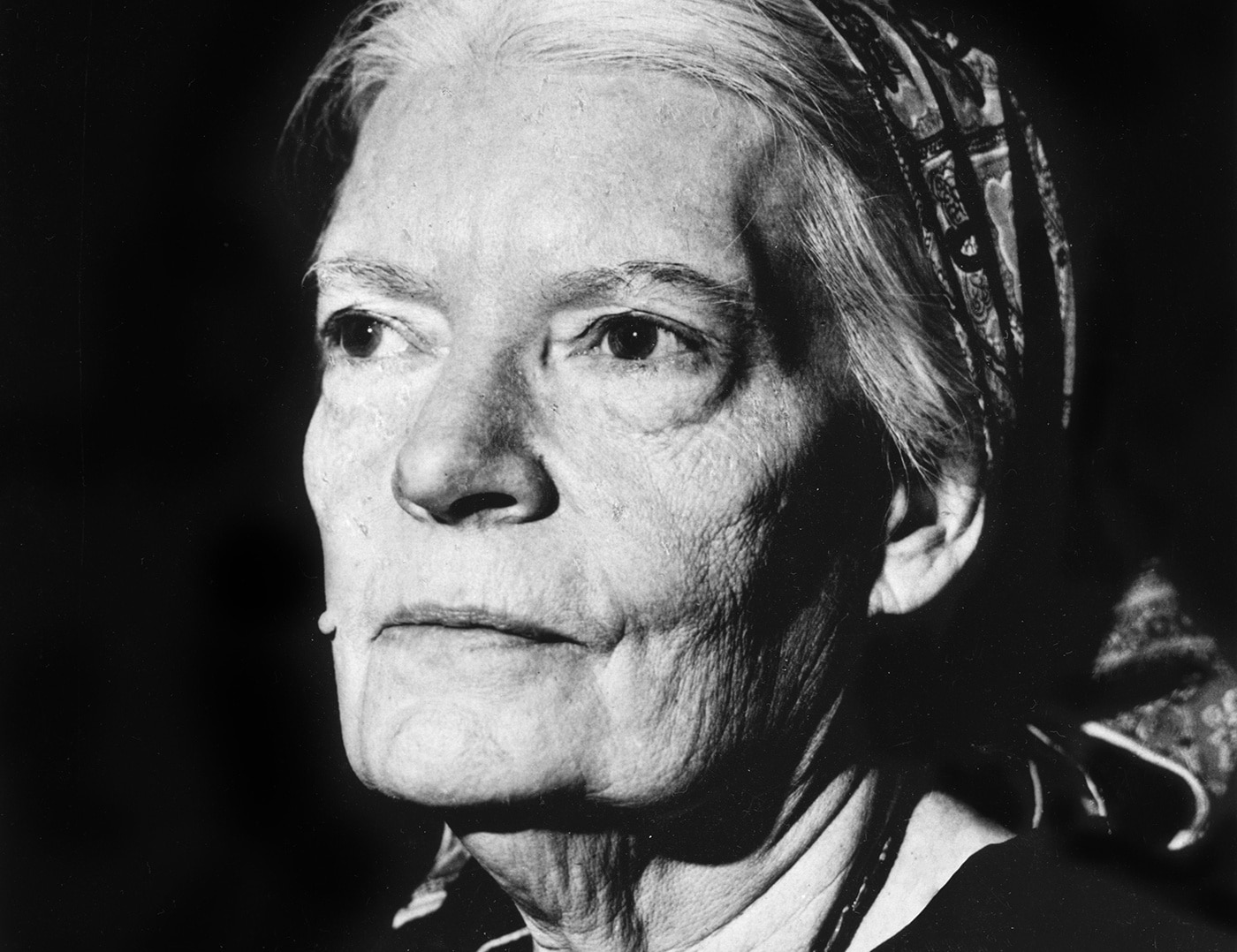

Dorothy Day once expressed her hope that she would never be proclaimed a saint, believing that if she were, individuals would cease to heed her words. Regardless of whether Day’s wish becomes a reality—at the moment of this writing, the proceedings that might lead to her recognition as a saint seem to be progressing in Rome—fascination with this proponent of a transformative approach to social justice shows no signs of waning. Recently, it has even escalated to the point, though still short of canonization, of naming a Staten Island ferry after her.

Most importantly, as the writers of a recent Day biography note, she was an individual who posed difficult inquiries: “Every assertion she made, every demonstration she participated in, her enduring dismissal of ease and convention, challenges us to consider: What type of world do we genuinely desire to inhabit, and what compromises are we prepared to undertake to realize it?”

Early life

Born on Nov. 8, 1897, in Brooklyn Heights, she was christened in an Episcopalian church, yet her parents later expressed no enthusiasm for her spiritual education. Nevertheless, from a young age, she exhibited an innate openness to spiritual matters. After learning about prayer from a Catholic neighbor, she started crafting her own elaborate prayers while she and her younger sister, Della, pretended to be saints — “It was a game for us,” she recounts in her memoir “The Long Loneliness” (HarperOne, $16.99).

Her father was a journalist whose work relocated the family to San Francisco and later to Chicago. It was in Chicago that Day, now a teenager, started exploring the works of authors like Upton Sinclair and Jack London, whose writings ignited her developing social awareness. Even at the age of 15, she noted, she sensed that “God intended for man to be joyful … we shouldn’t have to endure so much poverty and suffering as I observed all around.” While attending the University of Illinois, she became a member of the Socialist Party, deepened her engagement with radical literature, and scoffed at church attendees who showed no desire to contribute to a better society.

Bohemian lifestyle

Leaving university after two years, Day relocated to New York by herself and began her profession as a journalist contributing to Socialist publications. Right from the beginning, her articles revealed a sharp awareness of the visible signs of poverty combined with genuine compassion for the underprivileged. At times she reported on pickets, and other times she actively participated in the picketing herself. In 1917, she was involved in a women’s suffrage rally outside the White House in Washington, D.C., was detained alongside fellow demonstrators, and spent time in jail, where she perused the Bible and was profoundly affected by the psalms.

These were the years during which Day embraced the existence of an emancipated woman, mingling with journalists, authors, thinkers, and particularly with individuals from the left — anarchists, socialists, communists, and others. radicals. She also embraced a bohemian way of life where sexual promiscuity was considered the norm.

While Day might ultimately be recognized as a saint, her actions were far from virtuous. At one stage, she underwent an abortion — a traumatic ordeal that instilled in her a deep fear of infertility. Years later, reflecting from a standpoint of profound Catholic belief, she remarked that casual sex possessed “the essence of the demonic, and to plunge into this darkness is to experience a glimpse of hell.”

Embrace of Catholic faith

After obtaining $2,500 for the film rights to a book she had authored, Day utilized the funds to purchase a seaside cottage on Staten Island where she embraced a picturesque lifestyle in a common-law relationship with a reserved anarchist named Forster Batterham. At this point, she was engaging in regular prayers and occasionally participated in Mass. To her delight, she became expectant, and in March 1926, she welcomed a daughter whom she named Tamar Teresa, in tribute to St. Teresa of Ávila.

From the beginning, she was resolute about having her child baptized, but confronted with her partner’s resistance, she postponed it. One day, while strolling to the village to purchase groceries and reciting the Rosary, she encountered an elderly nun named Sister Aloysia. The pair developed a friendship, and Sister Aloysia consented to organize the baptism, while consistently admonishing Day: “How can your daughter be raised a Catholic unless you convert as well?”

The nun instructed her in the Catechism, and in July 1927, Tamar was baptized. The next December, with Sister Aloysia serving as godmother, Day was conditionally baptized and completed her first confession and Communion. As she had anticipated, the definitive split with Forster inevitably ensued.

She identified as a Catholic at this point, yet she was far from traditional. “I loved the Church,” she remarks in “The Long Loneliness,” yet she viewed it as a supporter of “the forces of reaction” that she, a leftist radical, found repugnant.

Tensions escalated as the Great Depression enveloped the nation. Following her coverage of a hunger march in Washington organized by communists, she bowed in prayer at the crypt church of the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception. The day was Dec. 8In 1932, on the day of the Immaculate Conception, Day notes, “At that moment, I presented a heartfelt prayer, one filled with tears and deep sorrow, pleading for a path to emerge so I could utilize the abilities I had for my fellow laborers and for those in need.”

The Catholic Worker

Then she went back to New York. And there, awaiting her arrival at the suggestion of a common acquaintance, she discovered Peter Maurin. Neither was aware at the time, but this marked Day’s pivotal moment — the Catholic Worker had come into existence.

Maurin was a French Catholic farmer and self-educated thinker who conceived a reform initiative merging radical social change with deep Catholic conviction. “He was my mentor, and I was his follower,” Day remembers.

Peter Maurin was set to pass away in 1949, but by that time, thanks mainly to Day’s enthusiasm and determination, the Catholic Worker had grown into an important force in American Catholicism, assisting not only the marginalized and underprivileged but also serving as a focal point for fellow activists and youthful visionaries. It was well-known for The Catholic Worker newspaper, which started printing in 1933 and was sold for 1 cent each, alongside its houses of hospitality, shelters for the impoverished and homeless, whose approach Day characterized as “living from day to day, taking no thought for the morrow, seeing Christ in all who come to us, striving literally to follow the Gospel.”

Day did not forsake her occasionally unpopular beliefs for the sake of societal approval. She declined to disavow the communists who had been her allies, supported pacifism and nonviolent approaches, and opposed the United States’ involvement in World War II as well as the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. An active participant in peace rallies, she was detained multiple times and in 1956 encountered the “nightmarish ordeal” of 30 days in a women’s detention facility.

Concurrently, she stayed loyal to the Church and its teachings. “I have faith in the Roman Catholic Church and everything she imparts,” she expressed. “I have embraced her authority wholeheartedly. … We are instructed that faith is a blessing, and at times I ponder why I possess it while others do not. I perceive my own lack of merit and can never be thankful enough to God for his gift of faith.”

Day passed away from a heart attack on Nov. 29, 1980. As stated in a biography released in 2020, there were at that time 150 Catholic Worker houses and farms in the United States and an additional 29 located in foreign nations, while The Catholic Worker had a distribution of 25,000. Day is interred on Staten IslandThe tombstone on her burial site in the Cemetery of the Resurrection states plainly, “Dorothy Day, November 8, 1897-November 29, 1980/Deo Gratias.”